Terrestrial telecommunications systems have historically operated in frequency bands below 6 GHz due to their balance between coverage, capacity and indoor penetration. Although there were some exceptions for WiFi systems.

However, these bands up to 6 GHz, called FR1, are saturated. Moreover, they do not provide the high bandwidths required for future services such as extended reality (XR) or volumetric video. This has prompted research and development of terrestrial communications systems in higher bands such as FR2 (24-52 GHz and 57-71 GHz), FR3 (7-24 GHz), high millimeter/subTHz (92-114.25 and 130-174.8 GHz) and THz (0.3-10 THz).

One of the key issues in the use of high frequencies is that equipment and devices must be affordable and energy efficient. One way to achieve this is by designing equipment based on commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) components as opposed to telecommunications equipment from more expensive manufacturers that, on the other hand, do not allow equipment specifications to be tailored to specific values such as transmit and receive frequency. On the other hand, high frequencies are very sensitive to distance, so it is essential to develop techniques to increase coverage.

Multi-band integration: highly tunable quantum sensors

However, having such a plurality of communication bands means facing the challenge of integrating them, i.e., that a single system can use, for example, FR1 and subTHz, since the electronic hardware components are incompatible. Quantum sensing technology based on the tuning of the RF bands to the atomic spectrum of Rydberg states allows the development of multiband sensors that, on the same hardware platform, detect signals in a very wide spectral range, which could go from FR1 to THz frequencies, overcoming this technological limitation of the hardware. They also offer extreme sensitivity to measure very low intensity signals, opening the way to multichannel optical detection for high performance applications.

Advances in radio frequency: efficient front ends and improved coverage

In mobile communications networks, the energy efficiency of a cell is related to the power amplification stages of its radio front-end. However, the most efficient power stages present linearity problems, which adversely affect cellular multicarrier signals. Linearizing the behavior of the transmit stages alleviates the power amplifier requirements. However, implementing this type of technique is a major challenge in scenarios with multi-antenna and high bandwidth systems, which are common situations at millimeter frequencies (mmWaves). Also, the technology used in power amplifiers conditions the efficiency and cost of experimental radio front-ends, a problem that is aggravated in mmWaves.

The alternatives to implement radio front-ends for sub-6GHz and mmWaves bands are difficult to miniaturize in a multi-antenna system and offer low energy efficiencies. In 6GDIFFERENT we design and develop prototypes of compact multi-antenna radio front-ends, capable of performing adaptive digital predistortion, and with energy efficiencies higher than those obtained with generic connectorized elements. In addition, schemes and mechanisms are investigated for coverage extension with multi-band application, i.e., that can be used both in the THz band and in mmWaves.

Techniques for coverage improvement in high bands

In low telecommunication bands, such as FR1, the allocated bandwidth rarely reaches tens of MHz, which is a major handicap for ultra-wideband services such as XR. High frequency bands allow access to bandwidths of several GHz, but with limited coverage due to propagation losses of the transmitted signal. Specifically, at THz frequencies, the path loss on a 10-meter link can exceed 100 dB, making communication over longer distances difficult. In addition, the transmission power at these frequencies is quite limited.

To alleviate this problem, without having to increase the transmission power, there are signal processing techniques that allow greater range. One of them reduces the phase noise in the receiver, which allows a clearer signal and increases the communication distance without affecting the quality On the other hand, there are different ways of sending the OFDM signal, used in 5G and expected in future 6G networks, called numerologies. The numerology indicates the bandwidth of the OFDM carriers, which can be 15 KHz in LTE (4G) and 15/30/60/120/240 kHz in 5G. In millimeter waves, 120 kHz and 240 kHz are used because of the need to handle higher bandwidths and higher frequencies. Higher numerologies reduce interference between OFDM carriers and this improves coverage.

Radio frequency quantum sensors: introduction to quantum sensors

Throughout the 20th and 21st centuries, quantum technologies have undergone a great development, to the point where they have started to be commercialized in some fields, such as telecommunications (in which quantum key distribution or QKD stands out) or quantum sensing.

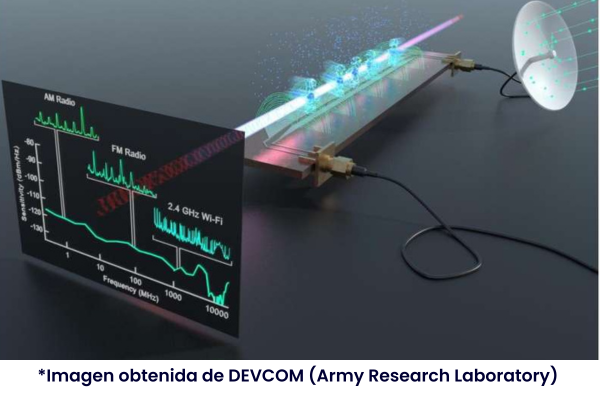

What are the parts of a radio frequency quantum sensor? On the one hand, it needs a container, usually glass, with a dilute gas of atoms of an element inside, usually an alkali metal, such as rubidium, cesium or potassium. A pumping laser excites the gas to a higher energy state. Then, an excitation laser drives the atoms to very high energy levels, known as Rydberg states. In these states, waves from the radio frequency spectrum can interact with the electrons, so that they absorb the energy of that external radio spectrum. This process has an impact on the amount of light from the pumping laser that can be absorbed by the atoms, making it possible to accurately monitor and measure the external radio frequency through an optical photon detector.

Advantages of quantum sensors

In the field of telecommunications, quantum sensors offer a number of advantages over classical antennas:

- Size, weight and power consumption (SWaP). A radio frequency quantum sensor is the size of a large box, occupying a volume of approximately 0.125 m3. On the other hand, most telecommunication antennas are between 5 and 15 m high, so the reduction in size is significant. A reduction in size implies a reduction in the amount of materials and their weight. In addition, these sensors require fewer components and consume an amount of energy comparable to that of a mid-range desktop computer, much less than that of traditional antennas.

- Resilience to electronic attacks. Being more resistant than conventional antennas to electronic attacks, RF quantum sensors can be used in both civilian and military environments, or even in environments where both coexist (dual environments).